On February 11, we mark the International Day of Women and Girls in Science by celebrating the women across UHN whose work drives health research and innovation forward. From principal investigators and trainees to administrators and support teams, their expertise, leadership, and dedication strengthen our collective pursuit of discovery for A Healthier World.

Join us in recognizing the remarkable women of TeamUHN whose contributions continue to shape the future of science.

Jennifer Boateng | PhD Student at UHN’s Donald K. Johnson Eye Institute

I am a fourth-year PhD student in the lab of Dr. Karun Singh at UHN’s Donald K. Johnson Eye Institute, where my research focuses on neuroscience, neurodevelopmental disorders, and autism.

Persistence.

Science is defined by failure as much as by discovery. Progress requires being comfortable with setbacks and staying motivated to move beyond them. When my experiments do not work, my curiosity and desire to answer my questions keep me moving forward. That same persistence has shaped my journey in research, pushing me to grow through challenges despite uncertainty.

What excites me most about my work is that we have access to innovative technologies that enable us to gain deeper insight into disease mechanisms. For example, in my lab, we use patient-derived stem cells to create brain organoids (lab-grown organ models) that help us to better understand disease onset and progression. Our research opens the door to precision medicine, where a patient's stem cells can be used to create individualized treatments.

Being a woman in science means representation and the responsibility of creating space for those who come after me. Scientific research has historically lacked Black women, and showing up confidently and doing meaningful work in this space can help challenge that absence and inspire others to follow similar paths. Being a woman in science also means gaining the tools to address issues that directly affect my community and using science to create lasting change.

To create a more inclusive environment, we need more mentorship programs to help girls early in their career learn how to successfully navigate the system. We also need support systems in place that enable women to focus on having families. Policies like maternity leave and childcare subsidies make it easier for women to confidently stay in science. I also think we must show how all kinds of women belong in science and that it is okay to be vulnerable and emotional.

Hold on to your ‘why’ and let that be what guides you. There will be many ups and downs, and there will be people who tell you that you do not belong in this space. In those moments, return to the passion and purpose that brought you to science in the first place. Your ‘why’ will be the anchor that keeps you moving forward.

Tatyana Mollayeva | Scientist at UHN’s KITE Research Institute

I am a scientist at UHN’s KITE Research Institute and lead the BRIDGE Lab, where we focus on equity‑driven research, education, and community engagement to advance brain health, particularly after traumatic brain injury.

Humility.

Humility has guided my lifelong path as a medical student, clinician, public health professional, researcher, and educator. It reminds me of how much I still have to learn, encourages me to ask questions, and fuels my curiosity. In my work and mentorship, humility helps me value diverse perspectives, fosters shared learning, and ensures our research remains patient‑centred, socially responsible, and grounded in equity.

I am most excited by research that focuses on prevention and equity across all stages of life. My work addresses early risk factors such as sleep and social determinants of health and uses clinical and population‑level data to inform policies and practices that can prevent injury, improve rehabilitation, and reduce long‑term burden. UHN’s vision of A Healthier World recognizes that equity and prevention are essential, not optional, and that deeply resonates with how I approach science every day.

Being a woman in science has deepened my sense of responsibility to those whose voices and experiences are often missing from research. The absence of evidence from historically underrepresented communities is not neutral—it signals who is seen and who remains invisible. I see it as my responsibility to ensure that this invisibility does not persist, and that science serves people across differences in gender, resources, and lived experience.

Creating supportive environments starts with early exposure and encouragement, showing girls that curiosity, persistence, patience, and creativity are just as valuable as speed or assertiveness. Within research settings, we must foster inclusive cultures that value collaboration, provide mentorship and sponsorship, and actively address barriers. Hands‑on experiences, community engagement, and peer networks help women and girls build confidence, resilience, and a sense of belonging in science.

Believe in yourself and your ideas—your curiosity and creativity matter. Be adaptable, ask questions, and don’t be afraid to challenge what you are told. Surround yourself with people who believe in you. Every step of learning makes you stronger and brings you closer to making an impact. Canada needs your vision and your talent, so go for it confidently and keep learning.

Heidy Morales | Research Quality Associate with the Research Quality Integration (RQI) department at UHN.

I work in the Research Quality Integration (RQI) department at UHN as a Research Quality Associate. I have previously worked in clinical research programs across various academic centres in Toronto, including in the fields of psychology, psychiatry, adolescent medicine, and hepatology.

Within my current role, I work closely with investigators and research teams through consultations, training sessions, and support during regulatory inspections. Our team plays a key role in strengthening regulatory compliance and best practice standards across UHN.

Collaboration.

In scientific research, collaboration is key to driving change and propelling new discoveries. My work requires building strong relationships with a broad range of stakeholders, including colleagues, trainees, scientists, research staff, and senior leadership. This ongoing collaboration is what makes my work a learning and rewarding experience.

Being able to contribute to the development and communication of research best practices and delivering education and support that promotes ethical, safe, and high‑quality research across UHN are the most exciting aspects of my work.

I strongly believe that knowledge-sharing and capacity‑building within the research community not only benefits scientists but also our patients and their families.

Being a woman in science means being multifaceted. From direct patient care, lab work, or administrative work, to supporting clinical research, each of us works to advance scientific development.

Being a woman in science also means being motivated by a passion for making a difference and understanding how we can support each other to elevate our contributions—building and advocating for equity and diversity through the work we do every day.

Collectively, we can create opportunities for women and girls in science through advocacy and sponsorship. By creating open and safe spaces for women and girls to network and meet others with varying degrees of experience, we can demystify what it means to work in science.

For women already in the field, having access to flexible work environments, opportunities for ongoing education and professional growth, and having ‘a seat at the table’ where key decisions are made is key. Representation at all levels matters.

My advice would be to stay curious and inquisitive. Showing an interest in learning and engaging with others’ work will open many doors. Being part of STEM means cultivating an open mind and looking for opportunities to learn while at the same time asking questions that may lead to new, transformative initiatives.

I recommend finding areas in STEM that fuel your passion and keep you grounded—seeking those who share your passions to start conversations with. Science needs all of us.

Emily Poulton | PhD Student at UHN’s Princess Margaret Cancer Centre

I am a PhD student at UHN's Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Dr. Marianne Koritzinsky’s lab. My research focuses on understanding how pancreatic tumours adapt and develop resistance to therapy, with the goal of identifying strategies that can improve treatment effectiveness and patient outcomes.

Leadership.

I was fortunate to be inspired early on by women in science, and that experience shaped how I approach my own career. I strive to pass that leadership and encouragement on to other women as they begin their research journeys, just as it was passed on to me.

What excites me most about research is that it continually challenges me to learn, think critically, and contribute to the broader scientific understanding of our world. Creating A Healthier World begins with understanding how biological systems function and how disease disrupts them. Our research focuses on overcoming pancreatic tumour resistance to therapies, with the goal of informing more effective treatment strategies in the future.

For me, being a woman in science means showing up with confidence and bringing my unique perspective into every space I enter. The women who came before us carved out opportunities through perseverance and hard work. It’s now our responsibility to continue pushing boundaries and redefining what women in science can achieve.

Early exposure to science and consistent encouragement play a major role in whether girls can envision science as a career. Supporting youth through meaningful engagement in scientific fields is essential, as is reinforcing that women are valued members of the workforce. These efforts help promote positive, inclusive experiences for women at UHN and beyond.

Stay persistent and do not back down. When doors don’t open, have the courage to open them yourself. You deserve to follow your passions and shape the life and career you envision. Simply showing up is already a powerful first step.

Dr. Stephanie Protze | Scientist at UHN’s McEwen Stem Cell Institute

I am a Scientist working in regenerative medicine and cardiovascular research using human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs).

Passion.

In my journey from undergraduate student to Principal investigator, I have consistently pursued what excites me and always worked with passion on research projects, which helped me accomplish my goals.

In my lab, we aim to harness the power of hPSCs to develop new therapies for cardiovascular disease. I am excited to work at the intersection of basic research and translation with the goal of bringing at least one of our stem cell-based therapies to the clinic during my career at UHN. These therapies will offer regenerative solutions and significantly improve treatment options, thereby contributing to UHN's vision of A Healthier World.

I am deeply grateful to my mentors who supported me throughout my career. As a woman and mother pursuing a scientific career, I appreciate living in an era that increasingly supports women, while recognizing that there is still work to be done. With that, I am committed to advancing and supporting the next generation of female scientists.

I strongly believe in the value of mentorship and in providing the tailored support that female trainees may need to thrive in their scientific careers, such as ensuring access to maternity leave and childcare. These supports benefit not only the trainee during important life transitions, but also their supervisor and the broader research team by maintaining continuity and stability within the laboratory.

My advice to young women interested in pursuing a career in STEM is to follow your passion and choose a path that truly inspires you. When you are driven by genuine interest, success naturally follows. I encourage you to seek out mentors and support networks that can guide you along the way—these relationships are invaluable to navigate challenges and reach your full potential.

Ayda Zokai | Research Administrative Assistant at the Latner Thoracic Research Labs, UHN

I am a Research Administrative Assistant in the lab of Dr. Marcelo Cypel at the Latner Thoracic Research Labs, UHN. I am also the co-lead of the AI and Big Data Sub-Committee within UHN's Research IDEA committee.

Unpredictable.

I could not have foreseen my career trajectory at UHN. From patient care to research, my path continued to evolve. Now, I have been given the ability to learn about IDEA (inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility) principles. I am grateful to my open and collaborative colleagues who brought me in and invested their time and energy to propel me forward.

Working on the Research IDEA Committee has become a passion project for me. I have had the opportunity to delve deeper into principles of justice, understand where gaps exist in the current health care system, and be inspired by the many ways we can continue to embed IDEA principles in all aspects of clinical and research processes. This work aligns with Research at UHN's commitment to “lead change towards an inclusive, diverse, equitable, and accessible (IDEA) research environment.”

It means providing a perspective that may not have been at the table otherwise. I have watched trainees come together in different ways to make sure women feel comfortable in male-dominated environments, and I have seen team building take on a different shape.

Through initiatives like UHN STEM Pathways, we can support and encourage a passion for STEM subjects from a young age. We can also create a more inclusive environment by maintaining an active focus on understanding and meeting the needs of women in our department. Sometimes, fostering belonging can be as simple as leaving space for those who have not spoken in a meeting. Seeing women bring their whole selves to the workplace and be honoured and uplifted is a huge point of inspiration to me.

It's okay to be seen and heard. Certain labs may be more male-dominated, but you have earned your place at the table just as they have. You are allowed to stand up straight during presentations and to ask questions and not apologize for it. Bring your unique self to the office—we are better for it.

Researchers from UHN’s Princess Margaret Cancer Centre (PM) have developed a new technique to rapidly identify molecules that bind to human protein targets. The method, called enantioselective affinity selection mass spectrometry (E-ASMS), is a highly sensitive screening tool that can detect even weak interactions between small molecules and proteins during the drug discovery process.

Traditionally, discovering possible drug molecules starts with high-throughput screening (HTS), where scientists use a variety of assays to test large libraries of chemicals against a protein target. This process often produces false positives—in which the assay suggests a chemical binds to the protein when it does not—and misses chemicals that bind weakly. Any compounds that show activity must then be confirmed through time and labour-intensive methods.

To address these challenges, the research team developed E-ASMS—an assay with improved sensitivity that works by using a clever twist: it measures how mirror-image versions of a molecule (called enantiomers) interact with proteins. Small molecules may come in two mirror‑image forms—like left and right hands—that can bind differently to the proteins they target. E-ASMS can detect when one form fits better than the other, called enantioselective binding.

To test E-ASMS, the team screened over 8,000 chemical compounds—50/50 mixtures of both mirror image forms of a chemical—against 31 human proteins, including many thought to be difficult targets.

They discovered 16 promising molecules that bind to 12 proteins, as well as solved the 3D structures of several of the protein-molecule complexes identified. Some of these proteins, such as HAT1, which is linked to cancers and developmental disorders, have long been considered nearly “undruggable.”

By detecting interactions that other methods often miss, this approach accelerates the discovery of new molecules from relatively small chemical libraries. In addition, detecting when only one mirror-image of a molecule binds provides an extra layer of evidence against false positives, reducing the need for extra tests.

The team plans to scale up the use of E-ASMS to screen thousands of proteins and create a massive machine-readable open database to accelerate global drug discovery efforts in the near future.

“This could transform how we find chemical starting points for medicines,” says co-senior author Dr. Levon Halabelian, Affiliate Scientist at PM and researcher at The Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC).

Overall, E-ASMS can help reveal hard-to-find chemical–protein interactions with speed and precision, opening the door to finding drug targets that have remained out of reach until now.

Drs. Jianxian Sun, Xiaoyun Wang, and Shabbir Ahmad are co-first authors of this study. Dr. Sun is a research scientist, and Dr. Wang is a Postdoctoral Researcher in Dr. Peng’s lab. Dr. Ahmad is a Scientific Associate at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre.

Drs. Hui Peng and Levon Halabelian are co-corresponding authors of this study. Dr. Peng is an Affiliate Scientist at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre (PM), Associate Professor in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Toronto, and a Scientist at the Structural Genomics Consortium – Toronto. Dr. Halabelian is an Affiliate Scientist at PM, an Assistant Professor at the Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology at the University of Toronto, and a Scientist at the Structural Genomics Consortium – Toronto.

This work was supported by the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the National Institute of Health, the Government of Ontario, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, and The Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation.

The Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC) receives direct member funding from Amgen Inc., Janssen Pharmaceutica NV, and Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, as well as grant funding from the Innovative Health Initiative Joint Undertaking, the Gates Foundation and the Michael J. Fox Foundation.

SGC also receives financial and in-kind contributions from Pfizer Inc., AstraZeneca UK Limited, Novo Nordisk A/S, Abcam Limited, Chemspace LLC, Enamine Germany GmbH, IBM Research Israel – Science and Technology Ltd., Nuvisan ICB GmbH, Thermo Fisher Scientific (Bremen) GmbH, The Hospital for Sick Children, and Vernalis (R&D) Limited.

Wang X, Sun J, Ahmad S, Yang D, Li F, Chan UH, Zeng H, Simoben CV, Green SR, Silva M, Houliston S, Dong A, Bolotokova A, Gibson E, Kutera M, Ghiabi P, Kondratov I, Matviyuk T, Chuprina A, Mavridi D, Lenz C, Joerger AC, Brown BD, Heath RB, Yue WW, Robbie LK, Beyett TS, Müller S, Knapp S, Owen DR, Harding R, Schapira M, Brown PJ, Santhakumar V, Ackloo S, Arrowsmith CH, Edwards AM, Peng H, Halabelian L. Enantioselective protein affinity selection mass spectrometry (E-ASMS) .Nat Commun. 2025 Dec 17;17(1):651. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-67403-2.

UHN has received a historic $27.1 million in total funding from the CIHR Project Grant Fall 2025 competition. The funding supports 31 research teams across UHN, including 24 full research grants and seven priority announcements.

The CIHR Project Grant program is designed to offer scientists, at any stage of their careers, funding for ideas with the greatest potential to advance health-related knowledge, research methodologies, patient care, and overall outcomes. In this recent competition, CIHR has invested approximately $413 million to fund 421 research grants across Canada. An additional 83 priority announcement grants were funded over $9.7 million, and 17 supplemental prizes were awarded a total of $450,000.

Among the UHN-funded projects are investigations into a new therapeutic target for acute myeloid leukemia (led by Dr. Steven Chan) and how BRCA2 mutations alter breast tissue before cancer begins (led by Dr. Frederico Gaiti). Other teams are studying immune pathways that are associated with age-related memory loss (led by Dr. Valeria Ramaglia) and developing new therapeutic strategies for retinal neurodegeneration, like glaucoma (led by Dr. Jeremy Sivak).

Some additional projects include determining which kidney transplant patients are most at risk of transplant failure (led by Dr. Ana Konvalinka) and identifying the challenges of personal support workers in Ontario to improve training, policy, and workforce stability (led by Drs. Nicole Woods, Sandra McKay, Maria Mylopoulos, and Stella Ng).

This funding is fueling innovations that lead to earlier diagnoses, more effective treatments, and stronger health systems. Thanks to CHIR’s support, UHN researchers are turning discoveries into real-world impact and helping create A Healthier World for all. Congratulations to all the awardees!

See the full list of the awarded projects here.

Biological tissues, like those in the kidney, are often organized into complex patterns, which are an integral part of how they function. A new study from scientists at UHN found that incorporating specific, intricate patterns in lab-grown kidney tissue can enhance how these models function and are used in research.

Kidneys filter the blood—removing waste and balancing fluids. Within the kidney, this filtering is done through networks of looping capillaries (tiny blood vessels), called glomeruli. Specialized cells called podocytes then wrap around these blood vessels using cellular projections called foot processes that branch from the main cell.

Podocytes provide a key filtration barrier. As they develop, podocytes' foot processes become increasingly complex. This complexity is an important indicator of podocyte health and function. Natural podocyte branching appears to follow fractal patterning—a form of repetition in which successively smaller copies of a pattern are nested inside each other, like tree branches.

These fractal patterns are not typically recreated in standard laboratory cell cultures—cells grown in a controlled laboratory environment that can be used as tools to test biological processes. Despite recent advancements, lab-grown models fail to replicate the complex 3D architecture of kidney tissue. This leads to models that are less functional and mature than those in the body, potentially hindering their use in the study of kidney function and disease.

As a proper 3D shape is known to influence podocyte growth and function, the research team explored whether incorporating a realistic architecture with fractal patterning in cell cultures could make lab models better and more representative of real kidneys.

First, by comparing detailed images of kidney cells, including podocytes, to fractal and non‑fractal shapes, they confirmed that healthy podocytes do indeed form fractal patterns in nature. They then created artificial textured surfaces that mimic these natural fractal patterns to grow cells on in the lab.

The team found that podocytes grown on these fractal surfaces showed stronger markers of functionality, had enhanced maturation, and organized themselves more like they do in the body compared to those grown on flat surfaces. Gene analysis also showed that these cells produced more of the proteins that make up the supportive material around them.

Overall, the results suggest that this approach to growing cells could eventually improve lab kidney models—advancing research in kidney disease and treatments.

Chuan Liu is a Doctoral student in Dr. Radisic’s lab and first author of the study.

Dr. Milica Radisic is a Senior Scientist at UHN and a Professor at the Institute of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Toronto. She is the corresponding author of the study.

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Center for Research and Applications in Fluidic Technologies, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, Additional Ventures, and UHN Foundation.

Dr. Milica Radisic is a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Organ-on-a-Chip Engineering.

Drs. Lieu, Konvalinka and Radisc are inventors on a pending US Patent application relating to fractal cues for cell maturation.

Liu C, Aggarwal P, Wagner KT, Landau S, Cui T, Song X, Shamaei L, Rafatian N, Zhao Y, Rodriguez-Ramirez S, Morton K, Virlee E, Li CY, Bannerman D, Pascual-Gil S, Okhovatian S, Radisic A, Clotet-Freixas S, Veres T, Sadrzadeh M, Filleter T, Broeckel U, Konvalinka A, Radisic M. Biomimetic fractal topography enhances podocyte maturation in vitro. Nat Commun. 2025 Dec 15;16(1):11116. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-66037-8.

In a recent study published in Rheumatology (Oxford), researchers at UHN’s Schroeder Arthritis Institute (Schroeder) examined how often people with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)—commonly known as lupus—develop pericarditis, and what the condition means for long-term health. Lupus is a chronic autoimmune disease in which the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissues throughout the body.

Pericarditis is an inflammatory condition of the pericardium, the thin sac of tissue that surrounds the heart. It is one of the most common heart-related complications in people with lupus. If left untreated, pericarditis can lead to serious long-term complications, such as fluid buildup around the heart or thickening and scarring that interfere with normal heart function.

Previous studies have struggled to consistently identify risk factors for pericarditis in lupus or predict disease severity and outcomes. To address this gap, the Schroeder team analysed clinical data from 2,122 patients followed at the University of Toronto Lupus Clinic between 1970 and 2024.

The researchers found that more than 20% of people with lupus experienced pericarditis, with nearly two-thirds of cases occurring within the first year after SLE diagnosis. Individuals diagnosed at a younger age and those with more severe disease were more likely to develop pericarditis.

Most pericarditis episodes resolved within about three months, and serious complications were uncommon. However, about one in six cases became chronic, and roughly one in four patients experienced recurrence.

Overall, these findings provide clearer insight into patterns among people with lupus who develop this potentially serious heart condition. While further research is necessary to confirm these trends and better predict who may experience persistent or recurrent pericarditis, this study lays important groundwork for earlier identification and more informed care for people living with lupus.

The first author of this study is Dr. Pankti Mehta, a rheumatologist at UHN’s Schroeder Arthritis Institute.

The senior author of this study is Dr. Zahi Touma, a Scientist at UHN's Schroeder Arthritis Institute, the Director of the University of Toronto Lupus Clinic at UHN’s Toronto Western Hospital, and an Associate Professor at the University of Toronto Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

Drs. Dafna Gladman and Laura Whittall-Garcia are also co-authors. Dr. Gladman is an Emerita Scientist at UHN’s Schroeder Arthritis Institute and a Professor at the University of Toronto Temerty Faculty of Medicine. Dr. Whittall-Garcia is a Clinician-Scientist at UHN’s Schroeder Arthritis Institute.

This work was supported by Lupus Ontario, the University of Toronto, and UHN Foundation.

Mehta P, Kharouf F, Carrizo-Abarza V, Li Q, Akhtari S, Harvey P, Osuntokun O, Whittall Garcia LP, Gladman DD, Touma Z. Prevalence, clinical associations, and outcomes of pericarditis in systemic lupus erythematosus: insights from the University of Toronto Lupus Clinic. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2025 Dec 13:keaf669. Epub ahead of print.

As a teenager in his home country, Morocco, Razq Hakem watched his grandmother suffer from an agonizing disease.

His family tried to shield him from the sadness of the situation. Years later, he learned she died of ovarian cancer.

While completing his PhD in France at the University of Aix-Marseille II, he also found out that two aunts and other relatives had developed aggressive breast cancers at unusually young ages.

“I didn’t know what subtype of cancer they had,” he recalls, “but it was similar to BRCA1-mutated cancer, which is also my research focus.”

These early encounters planted the seeds of a lifelong mission: to understand the genetic roots of cancer and to find ways to stop it.

Today, Dr. Razq Hakem is a Senior Scientist and the Lee K. and Margaret Lau Chair in Breast Cancer Research at UHN’s Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, recognized globally for his breakthrough work on BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and DNA repair mechanisms.

In the 1990s, scientists recognized that women carrying mutations on the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes had higher risks for cancer, but they lacked conclusive evidence linking the loss of these genes to specific cancers.

At that time, Razq had completed a PhD in immunology in France and a postdoctoral training program in immunology and genetics in the U.S. He arrived in Toronto in September 1994 to study the roles of BRCA genes in preclinical models and to uncover how their mutations are associated with cancer.

“Several top-tier laboratories were racing to publish the earliest discoveries related to BRCA1 mutations,” Razq remembers the fierce competition, and he was undeterred.

He deleted the BRCA1 gene in lab models, and the effects were detrimental. The team discovered that the loss of BRCA1 results in DNA damage, cell cycle arrest, and halted proliferation, rendering cells unable to survive.

Despite the exciting finding, Razq was frustrated as he could not study BRCA1 associated cancers, given that the cells in the lab models were dying prematurely. Therefore, he modified his experiments and deleted BRCA1 only in the mammary glands. After the modification, He observed a high incidence of mammary tumours, clearly indicating that the BRCA1 gene suppresses tumour growth in breast tissue, and that its mutations predispose for breast cancer.

He published these landmark results in Cell in 1996, and Genes & Development in 2004, followed by a series of studies that altered the global research focus toward understanding BRCA1’s role in DNA damage repair, replication stress and tumour suppression, which paved the way for targeted therapies.

“We were among the first groups worldwide to demonstrate the harmful effects of BRCA mutations and their link to breast cancer in preclinical models,” says Razq. “I am very proud of our achievements and grateful to our national and international collaborators.”

Razq’s lab has identified several potential therapeutic targets for treating cancers associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, two of which, RNF 8 and RNF168, are moving along the drug development pipeline.

His lab showed that loss of RNF 8 or RNF168 genes can inhibit breast and ovarian tumour development in preclinical models with BRCA mutations. They also revealed the underlying molecular mechanisms, involving the accumulation of DNA–RNA hybrids (R-loops), increased cell replication stress and genomic instability that can eventually lead to the death of BRCA-mutant cancers.

“Currently, BRCA-associated cancers are treated with different approaches, including PARP inhibitors and Platinum-based compounds. However, patients can develop resistance to these therapies, and there’s a need to come up with new treatments. Our discoveries point to novel strategies that can bring hope to those patients.”

The team also discovered a novel DNA repair mechanism that provided new insights for treating BRCA1-deficient cancers, in a collaboration with Dr. Karim Mekhail, a professor of laboratory medicine and pathobiology at the University of Toronto’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

They found that microtubule filaments from the cell cytoplasm can push the envelope of the cell nucleus, triggering tiny tubules to reach the DNA inside and catch most double-stranded breaks. BRCA1 mutant cells rely heavily on this mechanism to proliferate, and the team is trying to exploit this vulnerability to stop cancer growth.

Razq did not know what disease his grandmother had. His family tried to shield him from the sadness of the situation. Only years later, he learned she died of ovarian cancer.

This experience not only sparked his interest in cancer research but also in advocating for cancer awareness, especially in communities where cancer remains a taboo subject. “Times are different now—there is improvement in how we treat metastatic cancers, more knowledge of what genes are linked to cancer, and new ways to detect it,” he reflects.

“Keeping it hidden is dangerous,” he says. “Being informed can save lives.”

He remembers his grandmother’s suffering, the quiet agony behind closed doors. That memory reminds him that his work is never abstract. It is about real people, real families.

Razq recalls riding hospital elevators for work, surrounded by patients or families visiting loved ones. He recognizes the look of pain and the weight of fear. “They might be suffering because their parents or family members were at high risk of not surviving the cancer. That drives me to keep working every day.”

Meet PMResearch is a story series that features Princess Margaret researchers. It showcases the research of world-class scientists, as well as their passions and interests in career and life—from hobbies and avocations to career trajectories and life philosophies. The researchers that we select are relevant to advocacy/awareness initiatives or have recently received awards or published papers. We are also showcasing the diversity of our staff in keeping with UHN themes and priorities.

Image-guided surgery has transformed surgical procedures by enabling minimally invasive approaches and shorter recovery times. However, surgical precision during these operations depends heavily on the ability to accurately measure distances within the body during surgery. Researchers from The Institute for Education Research at UHN evaluated the feasibility and accuracy of a digital tool that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to support more consistent and accurate surgical measurements.

The research team developed a digital ruler using computer vision technology that allows AI models to analyze surgical video footage. The model identifies the tips of surgical instruments and calculates the distance between them based on the known size of the instruments. The AI model was trained using over 1,200 annotated surgical videos and evaluated against measurements estimated by surgeons and physical rulers used in simulated surgical settings.

The results showed that the AI-based tool had less variability than human estimates, especially over longer distances. The tool performed best when used with human oversight, where manual reviews and corrections were made to help the AI correctly identify instruments.

While the tool remains a proof-of-concept, the researchers anticipate future applications in the operating room through integrating on-screen measurements in surgical video feeds. The tool could also be used after surgery to help surgeons review recorded procedures and refine measurement techniques.

Overall, this study demonstrates the potential for AI-based tools to support more objective and consistent measurement during image-guided surgery, which may help improve standardization and quality of surgical care.

Raphael Kwok, first author of the study, is a research assistant in the lab of Dr. Amin Madani.

Dr. Amin Madani, senior author of the study, is an Education Investigator at The Institute for Education Research at UHN. He is also the Director of the Surgical AI Research Academy (SARA) at UHN and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Surgery at the University of Toronto.

This work was supported by UHN Foundation and the Temerty Centre for AI Research and Education in Medicine at the University of Toronto.

Dr. Amin Madani is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Allan Okrainec is a consultant for Medtronics and MedTech Syndicates, holds equity interests in GT Metabolic Solutions and Qaelon Medical, and receives honoraria from Ethicon.

Kwok R, Yoshida T, Hunter J, Laplante S, Brudno M, Fecso A, Okrainec A, Madani A. Development of an artificial intelligence based virtual tool for measuring distances during image-guided surgery. Surg Endosc. Epub 2025 Dec 9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-025-12461-2.

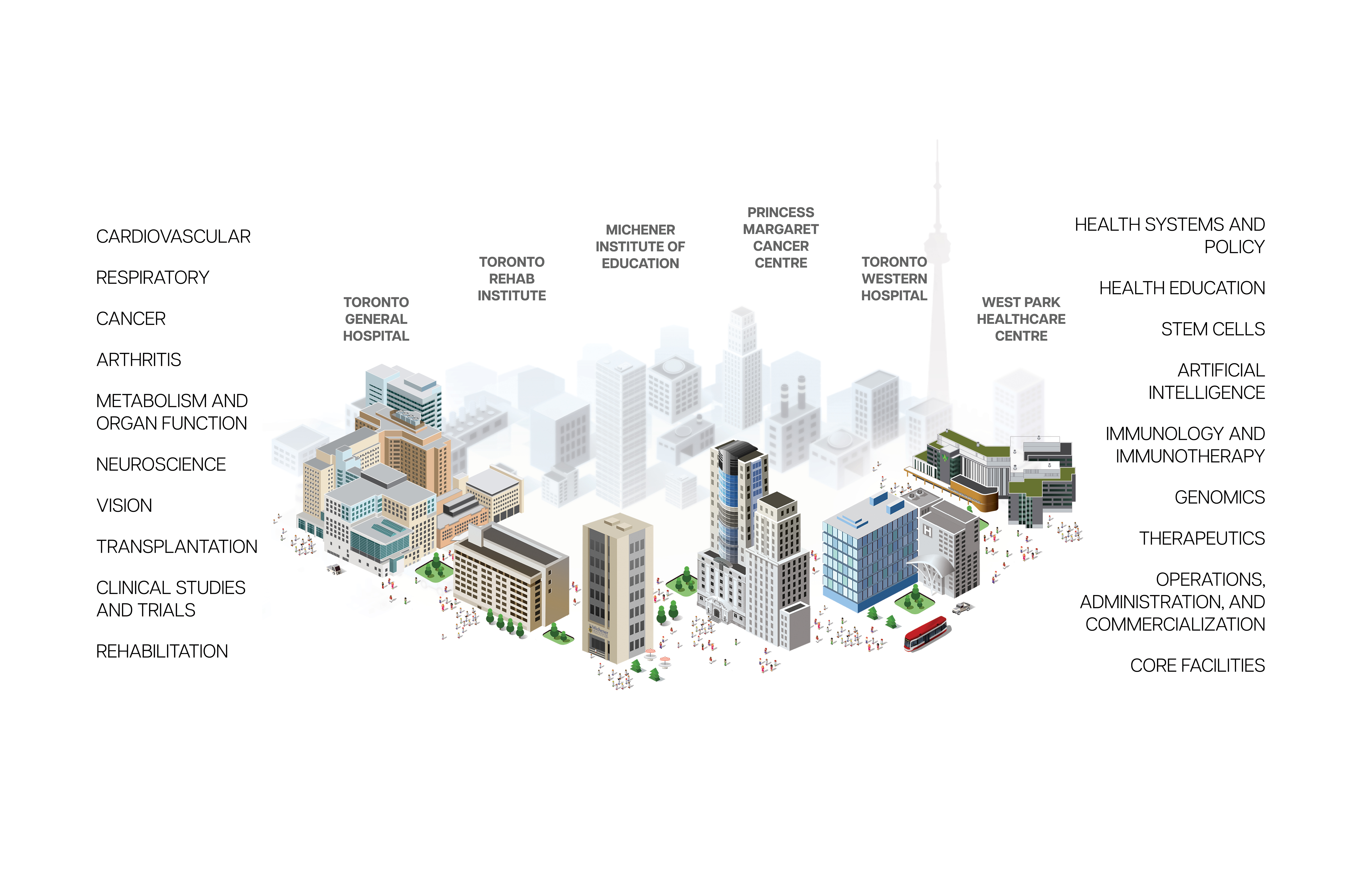

Research at UHN takes place across its research institutes, clinical programs, and collaborative centres. Each of these has specific areas of focus in human health and disease, and work together to advance shared areas of research interest. UHN's research spans the full breadth of the research pipeline, including basic, translational, clinical, policy, and education.

See some of our research areas below:

Research at UHN is conducted under the umbrella of the following research institutes. Click below to learn more: