Several genes, when mutated have the potential to cause cancer. More often than not, mutated genes work together to drive the development of the deadly disease.

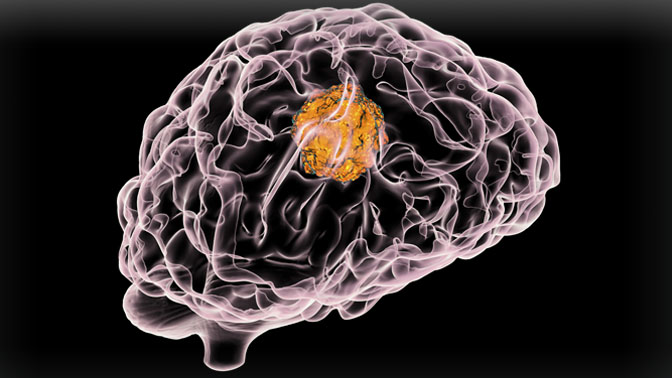

A new study led by Senior Scientist Dr. Tak Mak at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre reveals how genetic mutations contribute to the development of an aggressive form of pediatric brain cancer known as diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG).

These cancers arise in a type of brain cell called glial cells, which provide support for nerve cells that process and transmit information in the brain. Currently there are no effective treatments for DIPG.

“Genetic mutations are a hallmark of cancer,” says Dr. Mak. “Studying these changes in genes provides us with insight into how cancers arise and how they can be targeted pharmacologically, particularly for those cancers that do not respond to conventional therapies.”

While researchers understand the effects of common genetic mutations in DIPG tumours, others remain poorly characterized, including mutations in a gene known as ACVR1.

To address this, the research team created experimental models with the mutated gene and found that the ACVR1 mutation prevents glial cells from maturing from their precursor cells. Interestingly, this mutation alone did not lead to tumour formation. Rather, a combination of the ACVR1 mutation with other known gene mutations in DIPG led to the growth of high-grade tumours.

Working with scientists in the UK and the Netherlands, the team also used a drug to block the effect of the mutant ACVR1 protein, which reduced the growth of tumours in the experimental model.

“Here we show that by targeting this specific mutation and cancer-associated pathways, we can reduce cancer growth,” explains Dr. Mak. “Early-phase human clinical trials of this inhibitory agent have already yielded promising results in other solid cancers. This approach should be explored for the treatment of DIPGs.”

This work was supported by The Cure Starts Now, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation, the Fonds de la recherche en sante du Quebec, the Cancer Research Society, the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, Spirita Oncology, the Cancer Genomics Center Netherlands, the Netherlands Cardiovascular Research Initiative: the Dutch Heart Foundation, Dutch Federation of University Medical Centers, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences (RECONNECT consortium), FOP Friends, The Brain Tumour Charity and The Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation. Dr. Mak holds a Canada Research Chair in Inflammation Responses and Traumatic Injury.

Fortin J, Tian R, Zarrabi I, Hill G, Williams E, Sanchez-Duffhues G, Thorikay M, Ramachandran P, Siddaway R, Wong JF, Wu A, Apuzzo LN, Haight J, You-Ten A, Snow BE, Wakeham A, Goldhamer DJ, Schramek D, Bullock AN, ten Dijke P, Hawkins C, Mak TW. Mutant ACVR1 arrests glial cell differentiation to drive tumorigenesis in pediatric gliomas. Cancer Cell. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.02.002.