By Michael Chang, ORT Times Science Writer

Dr. Kyle Juraschka, a neurosurgery resident completing his formal clinician scientist training at the University of Toronto, says “In Canada, the two main paths for integrated clinician scientist training are either the MD/PhD program or the Clinician Investigator Program (CIP), and I am taking the latter route.” Dr. Juraschka explains the clinician scientist is a doctor who has received training in both medicine and research. They play a central role in working with both clinicians and scientists to translate discoveries from the laboratory to the clinic, and ultimately, towards impacting public policies that improve health outcomes. In fact, many successful research teams at University Health Network (UHN) are multidisciplinary and are comprised of basic scientists, clinicians and engineers. A recent example is the new Center for Advancing Neurotechnological Innovation to Application (CRANIA) at UHN, which is co-directed by Dr. Taufik Valiante, a clinician scientist himself. The value of clinician scientists at centers like CRANIA lies in their multidisciplinary training. They have the inquisitive nature to frame clinical problems they encounter as testable hypotheses; the practical aptitude to make data-driven decisions on potential treatment strategies; and the clinical capability to pilot novel treatments on patients.

Despite the integral role of clinician scientists in the Canadian health care system, there are major challenges to becoming a clinician scientist. On the individual level, the training is long and arduous. Clinicians who undergo additional research training to become scientists face lengthy training time and the mutually exclusive pressures of medical residency. On the systemic level, funding for clinician scientist training is being reduced. In 2016, the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) announced the end of funding for its MD/PhD training awards program. Given these challenges, it is not surprising that <2% of clinicians are active researchers. However, what is surprising is that ~50% of Nobel Prize winners in physiology and medicine in the last two decades are clinician scientists or had a clinician scientist on their research team. The disproportion of Nobel laureates who are scientists with clinical training signifies their importance in making ground-breaking research discoveries that can impact society. Canadian universities recognize this and continue to offer CIPs enfolded within residency programs for virtually every clinical specialty.

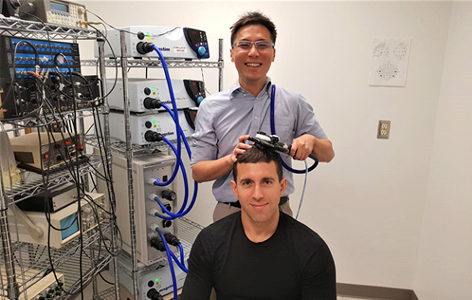

Dr. Anton Fomenko, another neurosurgery resident from the University of Manitoba CIP, is training to become a clinician scientist at UHN. He is pursuing his PhD in Dr. Andres Lozano’s laboratory at the Krembil Research Institute, where he studies new methods of deep brain stimulation using ultrasound waves to target individual brain structures in humans without the need for surgery. “The clinician investigator program has allowed me to immerse deeply into my research, and conduct experiments, which could one day be applied to brain disorders difficult to treat with surgery alone, such as Parkinson’s disease and epilepsy”, describes Dr. Fomenko when providing his thoughts about the program. Dr. Fomenko, who was recently awarded CIHR funding for his research, suggests that the Canadian government continues to value those in the crossroads of medicine and research.

CRANIA Co-founders, Drs. Milos Popovic and Taufik Valiante (Left to Right) at the BMO Education & Conference Centre in the Krembil Discovery Tower.

Dr. Anton Fomenko (bottom) studying focused ultrasound waves on brain activity with Dr. Stanley Chen, a neurology fellow, at the Toronto Western Hospital.